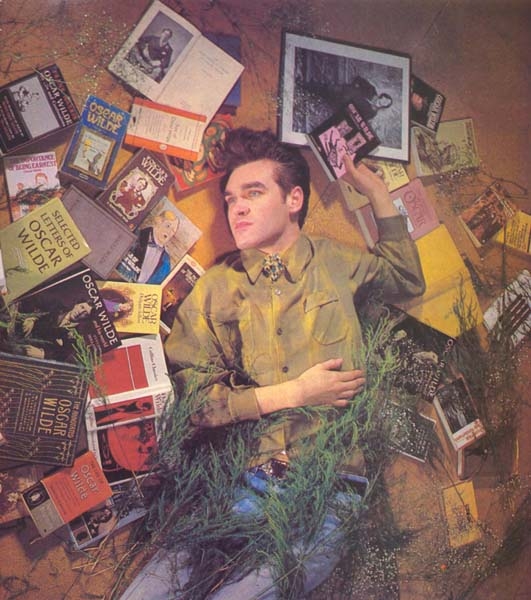

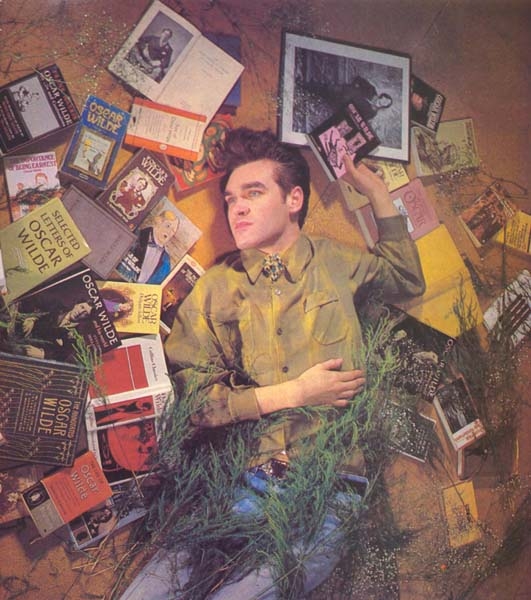

Image courtesy of Smash Hits

Number 4 in our series of blogs on the best ideas The Smiths had, the ones that changed pop and people’s lives forever. In the first blog, we argued that the band’s best idea of all was breaking up and staying that way, forever protecting their legacy. Blog 2 celebrated the band’s extraordinary b-sides while blog 3 took on sex in The Smiths, arguing that innuendo often provided a life and humour that was a key element of the band’s appeal.

This brings us – inevitably – to The Smiths’ lyrics as one of their great, defining ideas. And they were an idea: when he sat in his room and drew up his plan, Morrissey accomplished something which not even many novelists manage, let alone pop lyricists – he deliberately and meticulously designed his own lexicon, a way with words that became for thousands a way of seeing the world.

In fact, it was only during the long, tricky process of writing this blog that we realised the full scale of Morrissey’s achievement. We knew that he was a great lyricist, of course: that’s an accepted fact even amongst those who otherwise loathe him. But it was only when we went through the songs line by line that we realised how much work had gone into them and yet how effortless they seemed.

Let’s start with an obvious but crucial fact: when you hear a great Smiths lyric you know it can only be The Smiths. Others have tried to ape Morrissey’s style – Gene being the most glaring example – but always end up looking like clumsy shoplifters. Only Morrissey can write something as ornate and eloquent as “what she read: all heady books, she’d sit and prophesise” and follow it immediately with the lascivious earthiness of “it took a tattooed boy from Birkenhead, to really really open her eyes.”

Note too the loving reference to Birkenhead, surely its only appearance in song. As with many novelists but few pop singers, location was always a crucial element of The Smiths’ early lyrical universe. The ruffians had to be from Rusholme, failure must mean Whalley Range and if Manchester has much to answer for, that’s because Morrissey is always asking it questions. It was Northern England, particularly the North West, that provided the grit and wit that grounded Morrissey’s more exalted language. The idioms were there from the start of their career (“stay on my arm you little charmer”) to the bitter end (“who said I lied because I never – I never”). Indeed, it can be argued that the further Morrissey removed himself geographically from his loved/hated Manchester, the less distinctive his lyrics became – as later lacklustre solo lyrics suggest.

Continue reading →